The economic impacts of the former chancellor’s ‘fiscal statement’ of 23rd September, the subsequent u-turns and the resulting uncertainty and market disruption, continue to reverberate and have increased the chance of house price falls to a level not seen since 1990. But there are two UK housing markets: one is exposed to rising interest rates and the other is more insulated. Mortgage-reliant households will be under extreme financial pressure: from threatened recession, rising costs of living and now, significantly increased mortgage payments. For the 56% of owner-occupiers without mortgage borrowing, inflation and recession may be a problem but rising interest rates won’t be. This means the next housing market downturn is going to affect the mortgaged, mainstream markets with younger owners differently to equity-rich, prime markets with older owners. There are still reasons why buying a prime home may be among the ‘least bad options’ for protecting family wealth in the medium to long term.

Middleton Advisors commissioned Yolande Barnes Consulting (YBC) before the mini-budget to investigate the implications of rapidly rising inflation on housing markets. Barnes’s findings have particular importance in view of the market turmoil, rapidly rising interest rates and risk of recession which has arisen since 23rd September.

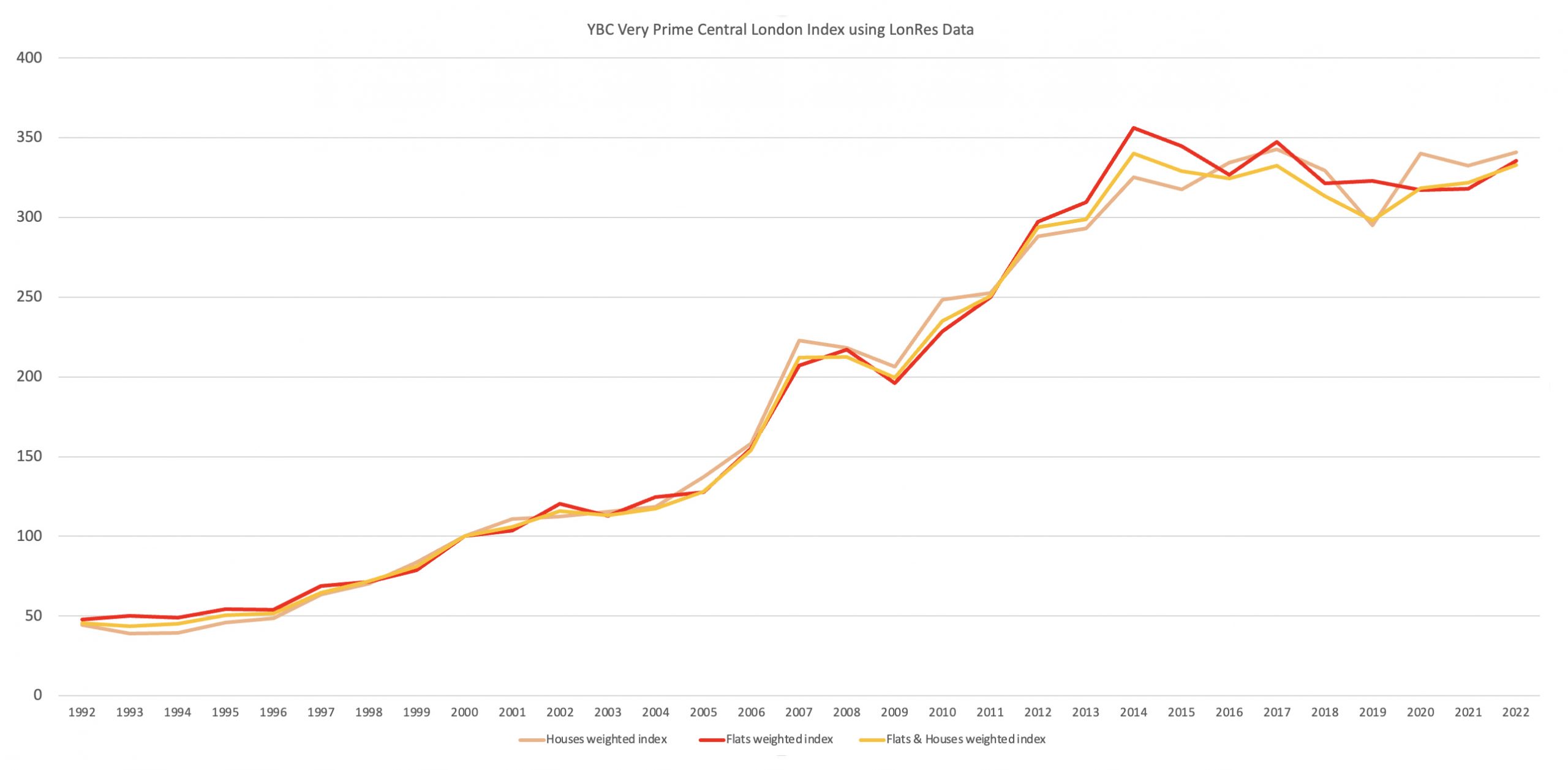

The research found that low inflation, and particularly the accompanying dramatic falls in interest rates, have driven house prices since the 1990s. In the very prime areas of central London, Barnes estimates that over half of the 629% price growth of the last 30 years can be attributed to falling interest rates alone.

Barnes claims “Most of this very high growth stopped in 2014, since when very prime PCL prices have been’ bumping around on a high plateau’. It is as if buyers in this market foresaw in 2014 that ultra-low interest rates would not last and anticipated the rising yields that have been seen in bond markets over the past two weeks”.

This means that house prices in the prime sector may not be as overheated as they are looking in some mortgage-reliant mainstream markets, she argues.

The research also suggests that real estate may be more resilient when inflation is rising than a lot of people expect. Looking back to the 1970s and 80s, when consumer price inflation was last at current levels, the data showed that house prices continued to rise when the price of other goods and services were also rising at record levels. “Broadly, mainstream house prices kept going up throughout the 1970s and 1980s even when consumer prices were rising at rapid rates” says Barnes “rising inflation alone does not mean falling house prices. What matters much more is the impact of recession and/or rising mortgage rates”.

The research concluded that real estate has many different characteristics for owners and, while the benefits in recent decades have centred around financial growth, housing can also provide amenity, utility, status and luxury value even when not automatically appreciating as a financial asset. Demand for homes that provide the right amenities has changed and grown appreciably since the Covid pandemic and purchasers of the good properties will enjoy these over decades of ownership rather than years.

“We expect house prices over this longer term to be driven by continuing demand for good homes and a relative scarcity of supply of what people want” concludes Barnes “This means that we will probably see the squeeze on household incomes and cost of mortgages reducing transaction levels significantly in the short term but not curbing latent demand for housing at all in the medium to long term. The market will probably polarise more between ‘the best and the rest’; between mortgage-reliant buyers and equity-rich buyers. (Over half of all owner-occupiers own outright, without a mortgage).

Significant and widespread house price falls will be seen only if recession and attendant joblessness and distress causes forced sales and increases the supply of available properties while it persists.

In these circumstances, cheap currency, distressed opportunities and longer-term demand prospects may make UK housing particularly attractive to oversea-funded investors who don’t mind holding sterling-denominated assets and who want sterling-related income. The long-term prospects for the currency will therefore be an issue in internationally-driven markets like prime central London.

For other types of buyers, the report points out that real estate could have some inflation-hedging properties. As other inflation-ridden nations have shown, there are huge benefits to owning and controlling a ‘homestead’. “One home will always be worth one home, whatever happens to economies, inflation or currency values” says Mark Parkinson, Managing Director at Middleton.